Also, November was a good month to wrap up a lot of television I was for some reason making time for. There are a couple of new shows - "Almost Human" and "Sleepy Hollow"; and it shocks me how much I'm enjoying those - and a few ongoing ones. Most notable were the Doctor Who 50th anniversary special, and, just this past week, the midseason finale of "The Walking Dead".

For those of you who may have been in a coma during the zombie apocalypse, this show (like the comic book it was based on) is about a fluctuating group of survivors following the pandemic infestation of a horrific and virulent disease. The world is now mostly populated by the undead, the flesh-eating mobile legions of zombies.

The creator, Robert Kirkman, wanted to do a comic book that took the concept of a zombie movie and kept going after the credits roll. He was constantly frustrated by the constraints of the zombie movies, because, as he explained it, "by the time you get to know these interesting characters, ROLL CREDITS."

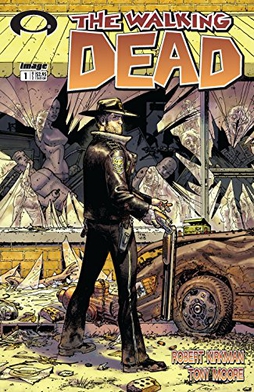

The comic started about ten years ago, and picked up a huge fanbase and audience, and won several awards. Fact is, it's some pretty heady stuff. It strays from conventional comic book storytelling (in addition to nobody being superpowered, of course) and applies one major rule: anything bad can - and likely will - happen to the main characters. No spoilers, let's just say you really shouldn't get too attached to anybody.

This clever and inventive storytelling picked up such a tremendous following that it was only time before someone tried to make it into a movie. Projects specs were thrown unabashedly at Kirkman, who remarked that most of them read like bad zombie movies - one, I believe, had a talking dog - which was ironic, since that was exactly the very sort of thing his book was intended to combat.

And then, Frank Darabont approached Kirkman with a much better idea: a television show.

So far, with a few dips and wobbles, the show has been quite satisfying. But I think the part I find most interesting is to compare and contrast the story of the comic book with that of the television show. Given my own projects, I find it interesting to see how storytelling becomes so dependent upon the medium.

I don't want to post details here - - some people are very anti-spoilers, and I'd like to respect that - - but the sort of things I find the most intriguing are the characters they use (and the ones they don't), the characters they kill (or maim, or leave pristine), and the individual stories they use, combine, change or leave out altogether.

See, some things just plain work better with whatever medium in which you're working. Look at fine art, for example. Recreating a beautiful sunset wouldn't work so well with sculpture, or pencil. You have to, to a certain degree, be willing to alter the original source in order to be best represented in the medium you've chosen. There are scenes in the comic book that just don't work as well on screen, so these have to be either adapted or abandoned. Comic books can be very limited because of their own, well, limitations. The Walking Dead comic book is all in black and white, for example, just like the old George Romero movies. AMC (the network that produces the Walking Dead TV show) even showed the first season in all black and white, as a kind of tribute marathon.

See, some things just plain work better with whatever medium in which you're working. Look at fine art, for example. Recreating a beautiful sunset wouldn't work so well with sculpture, or pencil. You have to, to a certain degree, be willing to alter the original source in order to be best represented in the medium you've chosen. There are scenes in the comic book that just don't work as well on screen, so these have to be either adapted or abandoned. Comic books can be very limited because of their own, well, limitations. The Walking Dead comic book is all in black and white, for example, just like the old George Romero movies. AMC (the network that produces the Walking Dead TV show) even showed the first season in all black and white, as a kind of tribute marathon.I stopped reading the comic when the show came out - I wanted to enjoy the show fresh, and not pick up any additional spoilers along the way - but I realized I was also now missing a lot of the "easter eggs" that the show runners were slipping into the series. So last night, I picked up my first three trade paperbacks and started them anew. It's been a few years since I'd read them, and I was pleasantly surprised at how well they held up as storytelling. I'd also been depressed at how much I'd forgotten about these early stories. Like, I'd forgotten all the character hookups, and how different these relationships had been there when compared to the show. That might sound like a silly thing to get hung up on, but here's the thing I think most people forget.

At its heart, this is NOT a zombie show. It's a people show. It's really all about how people react to the end of the world. Take out the zombies and replace them with nuclear fall out, or a forest fire, or boiling acid, or aliens, or rabid wolves. The story is about how people come to grips with sudden and permanent change.

Taken to its most personal level, think about the moment you realized that you were going to die. Like, specifically KNEW it. Everybody tends to have that moment, sooner or later, when you realize that the life you have had is gone, that you cannot in fact relive the past and that what lies ahead will never be like what has been. Sometimes, it's even more specific than that - you're diagnosed with something incurable, or lose a limb in an accident. Lose a friend. Lose a loved one. Admit to yourself that it's just never going to happen.

There is the old story about the man who was so wicked that the gods themselves conspired together to find an adequate way to punish him - and as a consequence of his deeds, they cursed him with the gift of prophecy. He laughed, recognizing that now he knew everything that would come to pass with a perfect clarity: he could see the future - not as it might be, but as it would be. "This is no punishment," he cackled, "this is a reward!" But then, he saw the moment of his own death, and, knowing that it was an unavoidable certainty, lived the rest of his life in abject misery. For to know one's end is a fixed point is to lose the most precious gift of all: hope.

One of the elements that is in the books but not so obvious in the television show is the eventual degradation

.jpg) of hope. In the first few books, a common statement is said: "when things get back to normal". It's not clear when this reflex ends, but it does end eventually. Over time, it erodes to the point of ineffectiveness - it is too weak and frail a thing to stand up against the realization that things will, in fact, never be the same again, that the Time of the Walker is here to stay.

of hope. In the first few books, a common statement is said: "when things get back to normal". It's not clear when this reflex ends, but it does end eventually. Over time, it erodes to the point of ineffectiveness - it is too weak and frail a thing to stand up against the realization that things will, in fact, never be the same again, that the Time of the Walker is here to stay. But in the television show, they are exploring different themes, in some cases much more subtle ones - - also, themes I believe the writers and producers now understand when looking back over the Walking Dead series as a whole which Kirkman could not have foreseen ten years ago.

Mostly, the one major theme the show is exploring is about what kind of person you become when faced with the end of the world. Where do your priorities fall, and what will you be willing to do to survive. It tries to address the question of "Hope versus Despair" in a unique way that the comic book is not always able to do. Granted, it has tools the comic book does not. It has an impressive and talented cast who can nuance an emotional response in a way that the comic book cannot; they have a soundtrack to help imbue the scenes with emotional subtext (not always effectively, but what are you gonna do), and it can pull focus to the exact place you need to go in order to get the story told to you in the way the writers and directors want you to see it.

The Walking Dead is a challenging concept to pace out, a complaint many fans have made. Consider this a moment. Once you've come to grips, as an individual, with the end of the world, what will then be required to change your perspective again? In that sort of an environment, how long does it take for habits to change, once newly established? Seems to me that you develop your "this is how we survive" habits, and everything else develops when you have time. You know, when you're not running for your life, or struggling to not die.

So when the different "chapters" of the show appear, they tend to advance the timeline by a few months, and we see all the characters adjusted to whatever new horrors they've faced, but they are established in those new (to us, at least) routines. And then, for several episodes, they don't really change so dramatically - or, if they do, it's only then at the end, when someone important to them dies. On the flip side, they can cram

enough intensity in ten minutes of screen time to fill up an entire graphic novel.

One last item, though. Characters on the show die. Again, I don't want to spoil anything, but, yes, main characters on the show die. They turn into zombies, are killed by friendly fire - sometimes not so friendly fire - and viewers get mad. It's an equation that can only lead to a sad and tragic end.

Coming from a writer's perspective, killing characters is NEVER an easy decision. You can't just kill them out of randomness, there has to be a point to their death - though, let's be honest, sometimes the point is to remind the reader that sometimes death is pretty pointless. A lot of folks will issue threats of "if you kill so-and-so, that's it, I'll never watch your show again!" which is both a compliment and an insult. As a writer, you want the people who read your material to love the characters so much that killing them will have an impact. But you also don't want people getting so mad at you for it that they stop trusting that the death MEANS SOMETHING.

George R R Martin lost me on a few of those deaths. He'd make me like a character only to kill them off by the end of that same introductory chapter. That makes me lose interest in even investing in future characters, period.

Joss Whedon ticked me off in the Serenity movie, too. Though I forgave him ultimately, there was a death or two which hurt. Like, almost tangibly caused me pain with their suddenness and brutality. As a fan, it stung. But as a writer? Man, I was impressed. The final act was filled with such juxtaposed hope and despair, that you truly just didn't know if they were going to come out on top in the end. You were anxious as they were, fearful that all their sacrifice would be for naught.

The difference between that movie and the Walking Dead, however...?

Serenity was a two hour movie, with a fixed resolution. The Big Damn Heroes would either triumph or die. No half-measures. But the survivors on the Walking Dead? What is their resolution? The truth is, they have none. Their success lies in survival, every week. If they survive, then they won the little victory. For their part, they have no choice but to try.

For me, the big question is whether or not the fans of the show will continue to manage their own sense of hope versus despair, and struggle each week with the characters, or if they, like so many of the characters so far, will simply succumb and be left behind.

Stay tuned.